The History of the Morris Island Lighthouse

Standing off the northern tip of Folly Beach is the Morris Island lighthouse, truly a sight to see and one that has a rich history.

Once located securely (or so it seemed) nearly 2700 feet inland, coastal erosion has washed away the beach so much that the lighthouse is now located nearly that far out into the Atlantic Ocean, with wind and waves awash at all times other than the lowest of tides.

The Morris Island Lighthouse is the oldest lighthouse in South Carolina, with the original light in that location thought to be placed by the first settlers to the area as early as 1673. The original navigational aid was simply a raised metal pan filled with pitch and set ablaze to help approaching ship captains find the entrance to Charleston Harbor.

That rudimentary light served its purpose until 1767, when King George III had a formal lighthouse constructed on the site. The new light was a brick structure that lasted nearly a decade but was eventually destroyed during the American Revolution.

After the war it was rebuilt and in 1789 it became the property of the United States Government, who maintained it and kept it updated with advancing technologies for nearly a century.

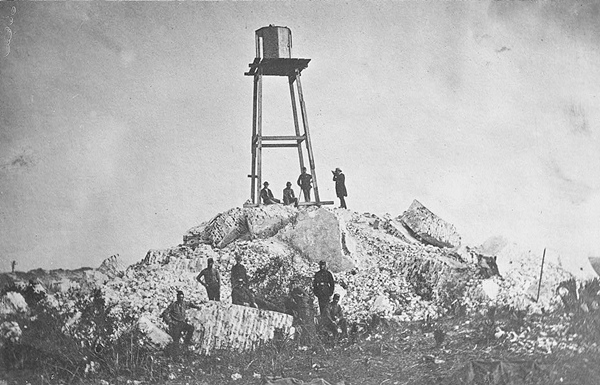

In 1861 the Civil War broke out and at some point the Confederate army seized every lighthouse along the coast in southern states. In 1861 the Morris Island Lighthouse was destroyed, and would not be rebuilt until 1873.

The aftermath of the Civil War, among many other things, left the coastline of Charleston a scrambled mess. The entire entryway to Charleston harbor had changed, and the old channels that existed prior to the war no longer existed, with new channels having opened up in their place.

Thus during Reconstruction, Charleston Harbor was wiped clean of all existing marks and lights, and new ones were installed to reflect the altered waterways. This led to the decision to replace the Morris Island lighthouse, as its location turned out to be ideal as an aid to navigation in the harbor.

In 1873 construction began on the Morris Island lighthouse, funded by the government at a total cost of $150,000.

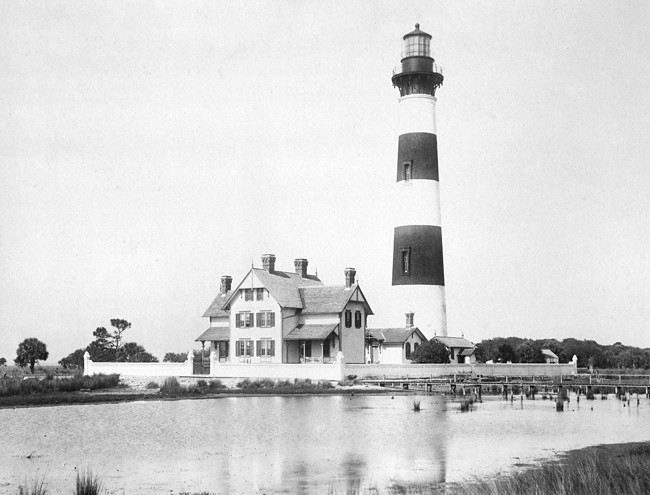

The new Morris Island Lighthouse, as it still stands today, was completed in 1876 and stands a total of 161 feet tall, making it the tallest lighthouse in South Carolina. It was built using the same plans as North Carolina’s Bodie Island Lighthouse, and thus was painted with the same black and white horizontal bands.

The Morris Island Lighthouse remained active until 1962, when it was replaced by the Sullivans Island Lighthouse, also known as the Charleston Light. The Sullivans Island Lighthouse was the last lighthouse built by the Coast Guard and is still active today.

Geographically Challenged

The decision to replace the Morris Island lighthouse with a new light on Sullivan’s Island was a long time coming, with Mother Nature slowly creeping up over the years until it became obvious that the light was doomed.

In 1889, construction began on the Charleston Jetties, which were built to protect Charleston Harbor and its shipping lanes from the wrath of the Atlantic Ocean. The jetties proved to be a critical element in Charleston’s success as a port city, but also had unforeseen consequences affecting the coastal landscape.

The main effect of the jetties, other than the benefits to shipping, were a total shift to the harbor’s already-strong currents. They jut out into the Atlantic ocean creating a funnel effect that causes rapid currents to rip past both Morris Island and Sullivan’s Island, drastically increasing their rates of erosion.

However, this effect was noted during construction, and there were plans set in place to create spurs on both the north and south side of the channel to protect Sullivan’s Island and Morris Island. The spurs were built on the north side and so Sullivan’s Island was saved, but sadly the spurs for the south end of the channel were never added, and the rapid erosion of Morris Island continued.

This wasn’t just from erosion due to currents, either. As residents of Charleston know, the city is located in a region that is prone to many mighty forces of nature. There have been several hurricanes that have impacted the lighthouse and further accelerated the island’s erosion, and it has even survived a major earthquake.

In 1886, the lighthouse and the rest of the Charleston area were subject to a freakish earthquake, measuring between 6.9 and 7.3 on the Richter scale. Much of Charleston was severely impacted, with many buildings still leaning over today as a result.

The Morris Island Lighthouse had some damage, though none of it seemed to impact structural integrity. In addition to several cracks in the foundation the lighthouse itself had cracks in two places as well as a shattered lens.

Still, the lighthouse kept on rotating, with a light keeper living on site full time. At least until the water came up far enough to threaten the safety of the residence. While the Coast Guard had done its best, there was little that could be done to stop the inevitable eroding of the land surrounding the lighthouse.

Automation & Retirement

By 1938, the entire 2700-foot span of beach that existed when the lighthouse was first constructed had been washed away, and the lighthouse stood at the face of the Atlantic ocean.

In the years prior to this, several preparations had been made for the eventual abandonment of the light keeper’s post on the island, so it could at least be done with some level of grace.

First, the keepers dwelling, hurricane-fortified as it may have been, was sold and then promptly dismantled and removed from the island. Most other structures, including a boathouse, telephone lines, and other various buildings were removed or burned to the ground before they could be washed away by the ocean.

In anticipation of the lighthouse being its own island, there was a 68-foot interlocking steel cylinder driven into the ground surrounding the brick tower itself. Finally, all electrical components were removed and replaced with an acetylene gas lamp that was fully automated.

From there the complex was mostly abandoned, but the light remained in service until June 15th 1962, and a few basic structures remained on the island for maintenance purposes. By this time the lighthouse had become mostly disconnected from the rest of Morris Island, and the light had been put to rest as the 140-foot Charleston Light on Sullivans Island was fully operational.

In 1989, the infamous category 5 Hurricane Hugo found its way into Charleston harbor, destroying everything in its path including the few remaining buildings surrounding the Morris Island Lighthouse. Only the dock remained until Hurricane Irma came along in 2017 and finished that off, though it has since been repaired.

The Morris Island Lighthouse Today

Since its retirement, the Morris Island Lighthouse has changed hands several times, with several individuals purchasing it starting in 1966. Real estate developer St. Elmo Felkel bought it for $25,000 and owned it until the late 90s (he also owned the Angel Oak for a time).

Then, it was acquired by Paul Gunter along with 80 acres of submerged land, and Gunter announced plans to sell the lighthouse along with the underwater land for $100,000.

Gunter was not successful in his attempt at selling the land, and instead it was purchased for $75,000 in 1999 by the newly-founded Save The Light organization.

Striving to conserve the lighthouse, Save The Light sold it to the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources for just $1, and then leased it back from them. This move allows U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to get involved with their efforts to stabilize and protect the lighthouse.

After 1962, the lighthouse was seldom lit again until 2007, when Save The Light began periodically shining the light to honor anniversaries and special occasions.

One exception to this was during the Spoleto Festival in 2002, when artist Kim Sooja managed to have the lighthouse lit as part of an art exhibit lasting from May 24th to June 9th. During this time the lighthouse was lit with floodlights that shined in white, red, green, blue and purple.

In addition to occasionally shining the light, Save The Light have also helped bring about efforts to improve the longevity of the tower.

2008 saw the installation of a cofferdam that surrounds the tower itself, sunk thirty feet into the sea bed and rising up fifteen feet above sea level at low tide. This helps protect the foundation from the day-to-day pounding from the waves.

2010 brought more major restorations to the lighthouse, including foundation repairs and the installation of 68 new concrete piles for additional foundation support.

The dock that was destroyed by Hurricane Irma in 2017 was repaired in 2019, and since hen restoration efforts have been focused toward the cast iron staircase on the inside of the tower. It has been eaten by the salt water over the years and is badly corroded.

Once the staircase is repaired, the team hopes to fully restore the lighthouse to a functional level. The estimated cost of conducting such a restoration is around $7 million, with an estimated time from of five years.

As of now, the lighthouse is by no means open to the public, but you can either take a boat tour or get a really good view for free by driving all the way down East Ashley to the Lighthouse Inlet Heritage Preserve. Park your car and walk the half mile or so and you can view the Morris Island Lighthouse from the beach, and take in all its historic glory!